Just for a change, I decided I’d go to a conference of a weekend… however, this time the conference WAS different. It was outside my area of academic expertise, and related to a novelist who I have read and re-read since I was around 10 (I’d read most “kids books” by that time, although I have to say Pride and Prejudice was maybe a step too far, and I’ve still never read it properly!). Georgette Heyer, however, is a great read! Her books are easy reading without being mush, well-researched historically, and bring the time (or at least one perspective of it) truly alive! The conference was fully sold out, with, I’m thinking 75 women and 5 men! A point that came up in the conference was that at the time Heyer was written, she was widely read by both men and women, including many well respected men (and her Infamous Army was a set text at Sandhurst for many years, and most MPs/those in the legal profession read her novels), but when the cover designs became more “bodice ripper” in style in the 1970s, the emphasis had changed from historical fiction to romance fiction, with an accompanying number of sneers at her writing! It was great to see so many academics talking about Heyer, for many of whom she is NOT their main source of research, but a side-interest, which I suspect contributed to the atmosphere and passionate interest in the conference, without getting bogged down in the minutiae of research, as can happen at many academic conferences!

Jennifer Kloester

Jennifer Kloester

Jennifer, who has been studying Georgette Heyer for 10 years (why did I never think that Heyer would be a suitable topic for a PhD, ah well, still love my posters!), had flown in from Melbourne for the conference. Excitingly, she has a new biography of Heyer with the publishers, and gave us a few tastes from it. Jane Aitken Hodge has provided the standard biography for many for years, but Kloester has had access to many more private papers, and other archival materials, and will be able to provide a more rounded study. Interesting to see how widely read Heyer is, especially in the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand - the cultural references clearly travel! At the end of the conference Jennifer gave us an insight into life post the publication of “Penhallow” (which had followed an Infamous Army and The Spanish Bride), for which Heyer expected to receive great critical acclaim in 1942, but instead received it for “Friday’s Child“, and afterwards wrote only Regency texts, as these were clearly what sold (Heyer loved writing what she perceived as the more biographical history, but tax burdens often forced her to focus on what sold). Jennifer gave us a great selection of information, but we’ll have to wait for her biography of Heyer to read it all! If you want to get the closest to inside Heyer’s head, the best read is suggested as Helen (which I’m now reading!).

Jay Dixon

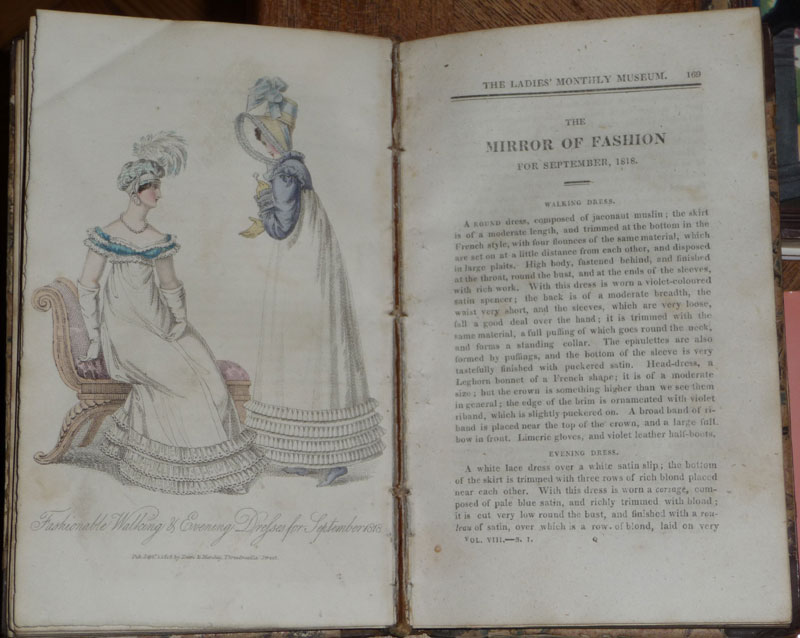

Jay Dixon, who used to work for Mills & Boon, has had a longstanding interest in Heyer, and conducted tours of Heyer spaces and places in London in 2002, the 100th anniversary of Heyer’s birth. Dixon gave us an overview of the description of place in Heyer’s novels, particularly of the South. In many cases the descriptions of geography are not long, but Heyer was able to sum a sense of Sussex in one sentence in a meaningful way. She reserved the levels of detail for stately homes, not even going into great detail for London. Freddy/Kitty carrying out a 2-day tour of London, with interesting rationales of why/why not to visit specific areas, but otherwise London descriptions are limited to a few particular spaces such as Almack’s, Rotten Row, St Jame’s Street, etc… essentially London is Mayfair, reduced to the status of a ‘village’, offering a social not a geographical space, where the ‘upper 500’ meet to do business. The country is idealised (feminine), whilst the city is seen as a noisy and disorientating space (masculine). London is offered as the centre of male power, where they have the freedom of the streets (women can’t go out without a maid), whilst Bath is an area where women can dominate, and live independently in a way they can’t in London. Heyer spent more energy on giving detail on clothes and the interior as she strove to conjure up a sense of period, whereas places change little… and the social spaces gave Heyer the space to be herself - psychologically.

Laura Vivanco

Laura is writing up amazingly detailed notes on the conference, which makes me feel less worried about writing so much here, as you can read more here! Laura’s starting point was that Heyer is often viewed as good escapism (suitable for reading in bed with the flu, with which I concur!), but that there is also a deeper level: Heyer has a number of estimable characters (often in the guise of governesses), who have a tendency towards intelligence and humour, which gives weight to the opinions that they have - and Heyer’s writings themselves are always well-written. It is clear from a number of characters that Heyer promotes education (for boys AND girls), and that upbringing is seen as important. Standen notes “how will you know the right way if you’ve never been taught it”, and Tiffany and Laurie were both “ruined by indulgence”. Ancilla Trent, that most estimable of governesses, see it as her duty to TEACH, she may use unorthodox methods, but her concern is that her charge will learn (a process I aim for in my teaching). The education that Heyer offers is subtle, as the didactic elements are below a humorous surface layer, so would appeal to those (such as Tiffany) who wouldn’t read such material in obvious moral homilies, as Deborah Lutz indicates - offers a moral way of living. Vivanco noted that Heyer rarely uses dates within her text, but that all texts DO have a clear sense of period, which can usually be established by a study of the dates of battles/existence of Royalty.

P.S. If you’re wondering what didactic is: “morally instructive” seems a good description!

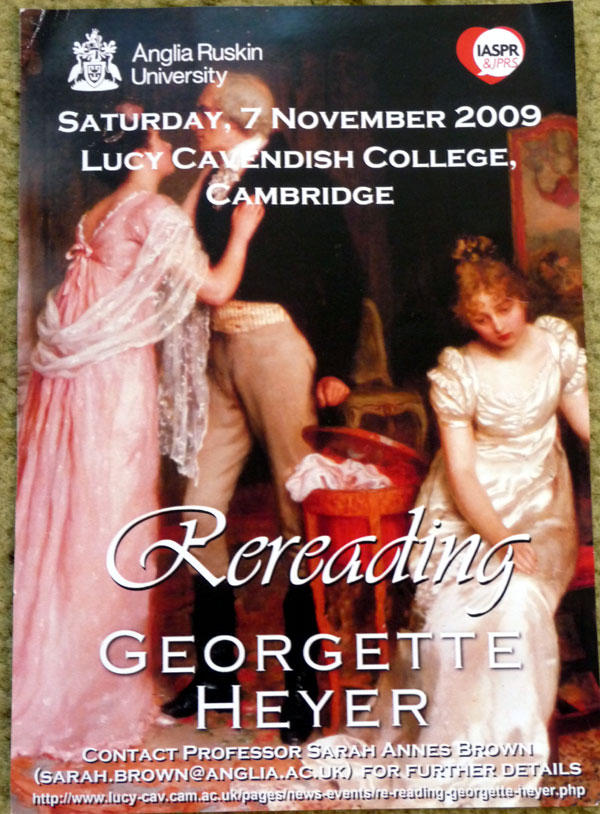

Sam Rayner

Sam Rayner, a specialist in publishing, gave us a fascinating insight into the changing covers of Heyer’s works (they’ve never been out of print since 1921), and how those changing covers have changed the way in which Heyer is received/read. The poster for the conference (above) was taken from “Cousin Kate”, one of Arrow’s most recently re-published works of Heyer’s Regency texts: all images from the series are taken from 18th/19th Century pictures, so as to give Heyer a “brand”. Heyer’s paperback works have always been published in A size, but for the most recent editions, a B Format has been used - a little larger (consequently a little more expensive, unfortunately!). Rayner’s favourite designs are the Pan covers of the 1960s, a kind of “cameo” design, but illustrated how the variety of designs have changed the fortunes of Heyer - for example a series of eau de nil hardbacks produced for libraries had a distinctive look, weren’t over-feminine, and don’t overstate the romance, and thus had a wide readership. A later series of paperbacks produced by Pan had very lurid covers influenced by Hollywood, and marketed at the lowest common denominator, appealing to “Adventure! Excitement! Romance”!, which also suffered from poor reverse cover blurbs (Heyer had generally written her own for the hardbacks), and Heyer had a particular distaste for “An Infamous Army”. Pan soon reworked the covers, introducing the ‘cameo’ designs, slightly less lurid, and with re-written back cover blurb. It’s generally clear which era the texts have been produced in, as e.g. those in the 1960s/70s have a distinctive look from that era, particularly noticeable in the hairstyles. After a series of other covers, in the 1970s a whole new look was given to the collection - and as books are very much judged by their covers, it was disappointing to see how insipid and chocolate boxy the designs were, stressing ladylike stories - attracting very much the wrong kind of reader (who Rayner indicated would have got slightly more than they bargained for - not your usual mush, but witty, well-written text). In 1991 Arrow took over and reproduced the series, reusing the cameo idea, with a refocus upon the architecture of the time, and giving a sense of the story - whilst adding a touch of class with gold lettering. In 2004-5, Arrow republished in the B-Format, with a more literary feel to the designs, a tactic which has been so successful that many other authors (Stephanie Laurens, Julia Quinn, etc.) have also capitalised with similar designs. The first print run had a number of errors in the text, which were then re-edited - and with current print methods it is possible to keep tinkering with the designs and adjusting any errors in the text.

P.S. This is a paper I would like to follow up. I’ve had on my to-do list for quite some time that I’d like to investigate why Heyer has remained popular for so long, and visual culture is a real fascination for me.

Mary Joannou

Mary Joannou

Joannu was coming to Heyer from a background of interest in Austen (wheareas I’m just starting to get interested in Austen after that failed tangle with Pride and Prejudice - I’ve seen all the videos, visited “Pemberley” near Manchester, visited Austen’s house in Chawton twice, seen Austen’s tomb/house where she died in Winchester - as I live there!). Austen had an intense moral preoccupation, but don’t forget that she was also comic, light-hearted and ironic - and as Mary said - not difficult to read, but playful! Heyer’s characters, however dangerous the situation, gives a quick-witted response. Heyer was writing throughout the depression, the 1930s, World War II, and writing for those who were living close to war/revolution. Heyer was also writing at a time when things were moving on from the seriousness of the Victorians, and there was a growth of the “middlebrow” during this period. Both Austen and Heyer were writing intellectual comedy, writing about tight/stable worlds where there were rules to be learnt. Heyer’s works are rarely dated, but include a number of events on which the stories can clearly be hung - generally stories which involve a number of events en route to marriage - but are those references to history any more than decorative? The clergymen in each Austen novel offer the underpinning morals of society, a role they rarely undertake in Heyer, who’s more interested in presenting style, fashion, prejudices and manners. Friday’s Child, written at a time of austerity, in particular takes delight in focusing on excess. Austen was interested in discourse, rather than the actual events, whilst for Heyer the events help offer a sense of period. We must remember that these are literary texts - TEXTS, not history - an artefact that plays games with history. Heyer could take as her blueprint Darcy/Elizabeth, who looked for an equality in marriage (rather than a financial transaction as many were in the 19th Century).

Pre-Lunch Discussion

Why had Heyer’s books not been made into films? Kloester noted that this was something that Heyer had always wanted, and both These Old Shades and The Grand Sophy are currently held on option by studios in the USA. All the others texts are held on option for TV series, and no one else can make them until those options expire! Apparently the BBC thinks that all Heyer novels finish the same way, and therefore a series should be done as Cranford! Kloester plans to write a screenplay for one of them! Meantime, here’s The Reluctant Widow (Heyer hated it!)

I can’t find the famous German version of Arabella, can anyone else - meantime, here’s a search for Georgette Heyer on YouTube!

Kerstin Frank

How was a talk on “the thermodynamics of Georgette Heyer” going to make sense?! Frank was discussing that at that time (and I guess still now), that cold was associated with the absence of motion, and a staticness, but as stories started to get moving, the story would “warm up”. Within such a polite society, warm feelings (such as those evinced by Arabella) were frowned upon. Society had a fascination for scandals - concerned very much with outward looks. The advantages of wealth/privilege allow a concern with clothing, as there’s no real issues to concern the participants… boredom has a large part to play in Heyer’s society (how many yawns!). Many characters despise fashion, but become fashionable simply by despising it. The hero is often seen as lazy, sleepy, drawling, etc. and props such as the quizzing glass often heighten this effect of coldness! It’s a static social dance in which the different personalities start to clash - causing the story to warm up. The coldness is often revealed to cover up pain, which has been stirred up by events. There’s a shared understanding of folly in society, which is constructed upon artificial/arbitrary lines. There’s a restricted space for challenging these constructs - and always tends to be within the private not the public sphere. Characters always want a marriage of love, rather than a marriage of convenience (largely unthinkable in those times) - but in the end they never have to choose as “blood will always out” - and they are discovered to have ‘appropriate’ family which allows the marraige to go ahead. Heyer is redeemed from romantic clichés through the scope of variations on a theme, and also by the constant self-parody/irony.

Catherine Johns

Catherine (an archaeologist) started this talk by indicating that the obvious can easily be overlooked - their opinions can’t expect to be the same as our own, and changes have happened extensively post-WW2, by which time Heyer’s opinions were largely formed. We read the novels/Regency period through a double-filter: through our time, and through the time that Heyer wrote them. To understand the time itself more closely, you need to read the contemporary novels (which Heyer had suppressed, but are still available as reprints from the USA). Heyer’s detective stories were variable in quality - giving her own perceptions of the time, especially Duplicate Death (1951) - when Heyer was particularly concerned with issues of extensive taxation. Heyer used national stereotyping extensively - her novels were largely comedies, and this was an accepted comedic device. She was making fun of a class system to which she fully subscribed - and often (as in the end of The Grand Sophy) was not being ironic, but was (modern parlance!) laughing out loud! The social stratification at the time that Heyer was writing (and about which she was writing) was far more visible at those times than it is now - and her definitions of hierarchy does not necessarily indicate the same thing as values - as a writer she is often consciously mocking assumptions. It’s an observation, rather than value judgements - we don’t like to admit an awareness of class/race and swath our conversations about that in euphemisms, but in Heyer’s time, there was more openness about this. Johns talked a lot about animal breeding, and the influence of the nature/nurture debate upon the way that Heyer would have been writing - when talking about a thoroughbred and a carthorse, neither was seen as better, but each as more suited to their role - as Heyer would have perceived - the Earl was not better than a ploughman, but more suited to his role, with an “innate sense of breeding” - and we can see this come out in the storyline of These Old Shades when genetics will out!

Sarah Anne Brown

Drawing upon the work of Eve Kosofsky Segwick, Brown indicated that for many at the time of Heyer’s writing/what she was writing about, men (in particular) were encouraged to have good male friendships (think boarding school), but that the homoerotic was to be discouraged - and there were worries that men would fall prey to homosexual desires. The womanly woman was able to live with a woman, and Brown drew upon Lady of Quality to indicate a fear of lesbianism indicated in Heyer’s novels, particularly the relationship between Annis (an independent woman), and Amabel ( her “lovely” mother-in law), and Lucilla (who becomes Annis’s charge, and whose hair is decorated “a la Sappho“)… where the implication is that Annis is going to be a bad influence. Those fears disappear as Annis’s friendship with Oliver (a marked rake) grows.

K. Elizabeth Spillman

Spillman wrote an MA thesis at Bangor on Heyer/Austen, and started her talk with a an idea that disguise, meant to conceal, can also reveal. Gender is performative (see Judith Butler). Heyer deals with disguise in many different ways, but there are three novels in which she particularly draws upon cross-dressing: These Old Shades, The Masqueraders and The Corinthian. Gender is a personification, signifying the real? In These Old Shade, does Leonie see herself as male of female (having been a “boy” for many years) - is it a part of her identity or is she dressing up? When Leon becomes Leonie, is she returning to her “natural gender” - she has fears about becoming a girl - and still continues as her male self in many way - and when she is kidnapped, managed to save herself by acting as a boy - leaving a question as to whether she would have been capable of this if she’d been raised as a girl. Much of the novel is concerned with instructing Leonie on how to “become a female” - so a clearly defined role. In The Masqueraders, those playing there part exhibit resignation not hate for their roles, and the first person in both novels to pierce the disguise is the future partner - Anthony has “an odd liking for her” (and therefore she can’t be a man, must be a woman!). In The Talisman Ring there’s also a small taste of cross-dressing - where the role is played to the hilt, but is not a central storyline. The Corinthian offers more comedy than melodrama, where there’s a breach of heteronormativity - more of an adventurous romance, and a comedy of manners (at which Heyer was very strong!). Debs Grantham in Faro’s Daughter can’t get back at Max as a “male”, so has to devise other strategisms - she’s used to more ‘unladylike behaviours’ (independence/initiative) - so in getting back, she’s not contravening normality by mimicking maleness!

Post-Conference Discussion

No one was quite ready to go at the end of the conference, so the discussion continued for a big longer!

- Heyer was unusual for her time - she was married. 9/10 women in some classes didn’t marry in that era because of the shortage of men who didn’t return from the First World War - the Officer Class was disproportionately hit, and many women needed to “marry down” if they desired to marry (check out Virginia Nicholson “Singled Out”).

- Bath was no longer so fashionable by the later Regency period, so it was more acceptable for women to live alone there. Particular novelists are associated with particular areas (e.g. Dickens, London; Austen, Bath)

- Detective novels were quite ‘boyish’, and fitted in with quite a number of school stories. The 1920s was the ‘androgynous decade’. In girlhood, many girls tried to be as like a boy as possible!

- What was the fascination with grey eyes? Her father had them? Coolness? Medieval historical convention: “Gris” meant sparkling/twinking - been mistranslated and therefore become a typical stylistic tool for novelists.

- Heyer has deliberately not described too closely, so that her readers can imagine.

- A peer reviewed journal “Journal of Popular Romance Studies” currently has a call-for-submissions for its inaugural Winter 2010 edition. The Journal is likely to be online only.

- The men in the audience tended to have picked up the novels from their mother’s shelves, although a couple of women indicated that it was their father’s who had inspired them with interest. Heyer is seen as a great writer, understanding the male psyche, and often appeals to science fiction readers.

- Georgette Heyer had very few close women friends, whilst Jane Austen had lots - can see in both writings!

- The conference finished with this great link:

Further Links

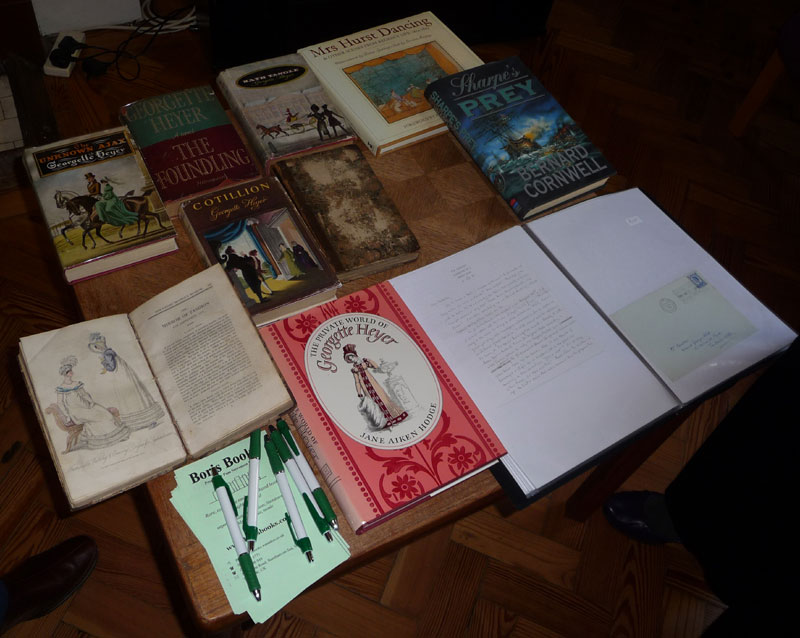

- Boris Books (including genuine fashion plates, and Georgette Heyer in a number of editions)

- Middlebrow Network (an AHRC network based at the University of Strathclyde, investigating the term “middlebrow”): “The B.B.C. claim to have discovered a new type, the ‘middlebrow’. It consists of people who are hoping that some day they will get used to the stuff they ought to like.” Punch, 23 December 1925.

- Prof. Sarah Brown’s weblog: Advertising the conference; Summary of the day; Questionnaire Results

- Alison Flood, Guardian: Which authors are worth a whole conference?; Guilty Reading Secrets.

- Diana Wallace: The Woman’s Historical Novel: British Woman Writers 1900-2000

- Lifeline Theatre, Chicago, which has put on a number of Heyer novels in the past.

- Review of The Corinthian by “enchantedbyjosephine”

Pingback: Georgette Heyer Conference | Rachna

I really enjoyed reading your summary because it was interesting to see how the papers had come across to you. Can I just mention, though, that I didn’t want to give the impression that all Heyer’s governesses are like Ancilla Trent. Heyer has an extremely silly governess in Cotillion, for example. Miss Fishguard doesn’t seem to have much intelligence or much of a sense of humour. The governess in The Grand Sophy is disapproved of by Miss Wraxton (though that doesn’t really mean much, since Miss Wraxton disapproves of an awful lot of people) and she’s depicted as a rather nervous, gentle person. The focus certainly isn’t on her teaching abilities.

Thanks Laura. Yes, what we say and what people hear are 2 very different things. I don’t think I meant to say that I thought that you said (sorry, that’s convoluted) that all governesses were like Ancilla Trent, but of course it was Ancilla that you concentrated on most. REALLY interesting! Meantime, I’m wondering, did we see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TOFps_Naytg, rather than the video I’ve tagged?! And excuse all my spelling mistakes, etc. I think I may leave them for posterity!

Pingback: drbexl.co.uk » Blog Archive » Georgette Heyer is featured in @timeshighered

A piece worth checking out - http://pictorial.jezebel.com/the-regency-romance-how-jane-austen-kinda-created-a-1731085396